K 1 = constant necessary to obtain the right dimensions. V = molar volume based on the method developed by Fuller et al.

The FSG method is based on the following equation: Its accuracy is poorest for polar acids (12%) and glycols (12%) and minimal errors are found for aliphatics (4%) and aromatics (4%) (Lyman et al., 1982). It is most accurate for non-polar gases at low to moderate temperatures.

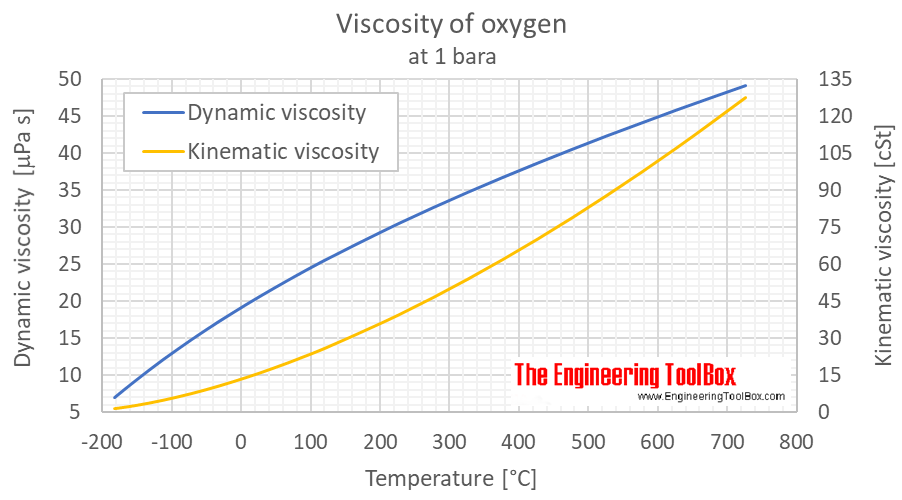

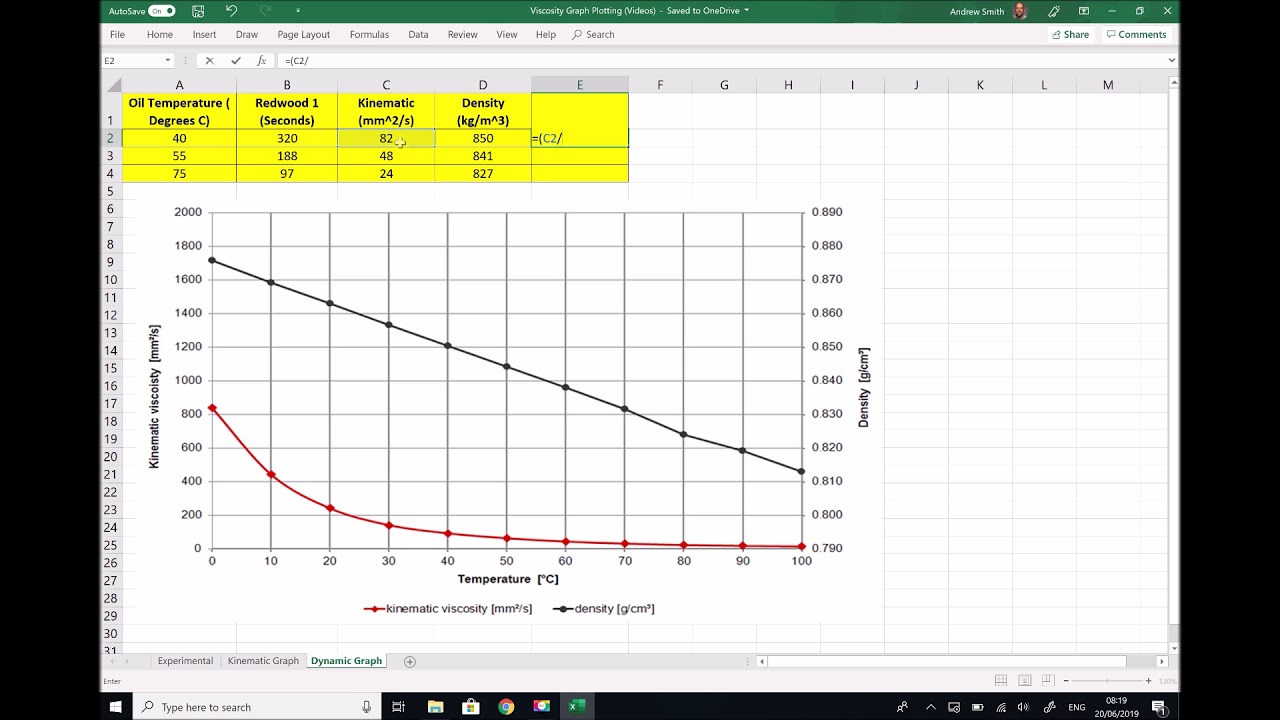

The diffusivity of a gas in air can be estimated by the method of Fuller, Schettler and Giddings (FSG method) (Lyman et al., 1982). Viscosity and kinematic viscosity of (sea)water Viscosity of air and water and estimation of diffusivity of pesticides in air and water Diffusivity of gaseous pesticides in airĭynamic viscosity and kinematic viscosity of air | Front page | | Contents | | Previous | | Next |Īppendix B. In the Couette flow, a fluid is trapped between two infinitely large plates, one fixed and one in parallel motion at constant speed u can be important is the calculation of energy loss in sound and shock waves, described by Stokes' law of sound attenuation, since these phenomena involve rapid expansions and compressions.Dry deposition and spray drift of pesticides to nearby water bodies Although it applies to general flows, it is easy to visualize and define in a simple shearing flow, such as a planar Couette flow. Viscosity is the material property which relates the viscous stresses in a material to the rate of change of a deformation (the strain rate). For instance, in a fluid such as water the stresses which arise from shearing the fluid do not depend on the distance the fluid has been sheared rather, they depend on how quickly the shearing occurs. In other materials, stresses are present which can be attributed to the rate of change of the deformation over time. Stresses which can be attributed to the deformation of a material from some rest state are called elastic stresses. For instance, if the material were a simple spring, the answer would be given by Hooke's law, which says that the force experienced by a spring is proportional to the distance displaced from equilibrium. In materials science and engineering, one is often interested in understanding the forces or stresses involved in the deformation of a material. In a general parallel flow, the shear stress is proportional to the gradient of the velocity. A fluid that has zero viscosity is called ideal or inviscid. Zero viscosity (no resistance to shear stress) is observed only at very low temperatures in superfluids otherwise, the second law of thermodynamics requires all fluids to have positive viscosity. For example, the viscosity of a Newtonian fluid does not vary significantly with the rate of deformation. However, the dependence on some of these properties is negligible in certain cases. In general, viscosity depends on a fluid's state, such as its temperature, pressure, and rate of deformation. For a tube with a constant rate of flow, the strength of the compensating force is proportional to the fluid's viscosity. This is because a force is required to overcome the friction between the layers of the fluid which are in relative motion. Experiments show that some stress (such as a pressure difference between the two ends of the tube) is needed to sustain the flow. For instance, when a viscous fluid is forced through a tube, it flows more quickly near the tube's axis than near its walls. Viscosity quantifies the internal frictional force between adjacent layers of fluid that are in relative motion. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of "thickness": for example, syrup has a higher viscosity than water. The viscosity of a fluid is a measure of its resistance to deformation at a given rate.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)